Account Login

Forgot your password?

Register for an account

XEnter your name and email address below.

Your email address is used to log in and will not be shared or sold. Read our privacy policy.

X

Website access code

Enter your access code into the form field below.

If you are a Zinio, Nook, Kindle, Apple, or Google Play subscriber, you can enter your website access code to gain subscriber access. Your website access code is located in the upper right corner of the Table of Contents page of your digital edition.

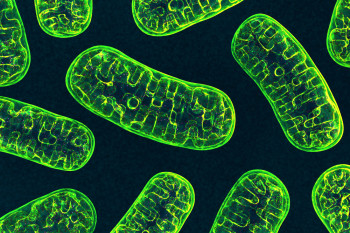

Gene Expression

Recommendations From Our Store

Stay Curious

Subscribe

To The Magazine

Save up to 70% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Copyright © 2021 Kalmbach Media Co.